I talked to Sam Perry, a Research Fellow at the University of Southampton, about scientific writing. Sam shared what helped him to develop his writing practice and described the process he uses when writing papers.

Hi Sam! What are you working on at the moment?

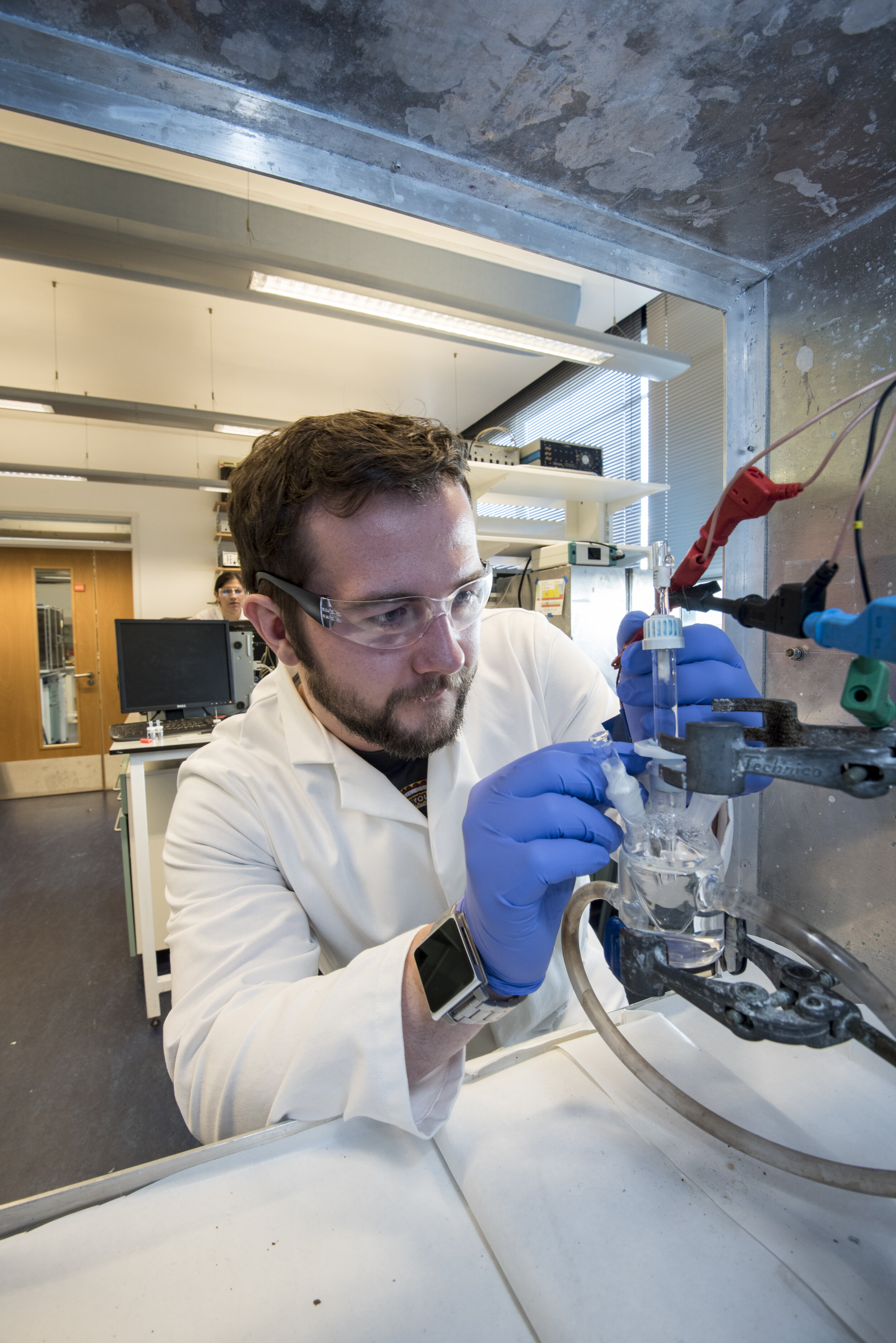

I’m on my second postdoc right now, at Southampton University. I’m working within a Horizon 2020 project together with a lot of different European universities. Our team is working on carbon dioxide reduction catalysis. I’m partly supervising a PhD student and a few masters students as well.

What is your research about more precisely?

The big picture research idea is trying to convert carbon dioxide into something useful. The product we are aiming for is ethylene, an important industrial precursor. It is used in the manufacturing of a lot of things like soaps and detergents, plastics etc. It normally comes from fossil fuels. Producing ethylene from carbon dioxide has two benefits: We use carbon dioxide that would otherwise get released into the atmosphere and we reduce dependencies on fossil fuels.

That sounds amazing!

Yeah, but it isn’t as easy as it sounds. We are using electrochemistry and copper electrodes for the reduction of carbon dioxide. But in this reaction, you get a mixture of lots and lots of different products, somewhere between 10 and 16 different ones depending on your reaction conditions.

So, the big challenge for the field of carbon dioxide reduction is trying to selectively make just ethylene. Our group is looking at little surface modifications in the copper catalyst to increase the ratio of ethylene that is being produced.

What would you say is your relationship with writing?

I think it is a bit of a complicated one because the job I have right now is so strongly research focused. Finding the time to write journal articles is usually easier for me than to write grant applications. I’ve tried to work around this by setting aside time to get into writing as a solid “event”.

Do you have a system for writing or a writing practice?

My default writing is incredibly verbose. So, when I’m writing, I try to just keep my train of thought going in the understanding that anything I write, I’m going to need to go back over and cut down.

I find that is generally a productive way of writing! And it’s something I do struggle with myself, part of me always wants to get each sentence perfect before moving on.

Yeah, it does take some conscious effort because it’s very tempting to reanalyse every sentence as you’re writing it.

Exactly.

But it’s amazing what edits you can make when you are looking at your writing with fresh eyes.

Yes! I always start writing by editing what I wrote the day before. That’s incredibly effective for me.

That’s one of the reasons I like to have bigger documents in the background for a longer period of time, rather than trying to get a paper or proposal out in a very short length of time. I find it much more productive to repeatedly dip into the writing with “refreshed eyes”.

Do you write for longer periods at once or use shorter intervals? And do you have any specific time of the day when you like to focus on writing?

It depends on what stage I am in the process. When I’m writing the initial draft, the most important thing, to me, is to keep that train of thought constant while writing and not breaking. After I have written the story, meaning when I’m in the editing stage, I like to dip back into it frequently. I’m fairly flexible in terms of when I do this. It’s normally based around my other commitments, like lab works, lectures and meetings.

I find that a quick-paced skim just before a lecture or a meeting is quite a productive thing for me. When I’m trying to read through the sentences a bit more quickly, I notice when I stumble when reading a sentence. Often that’s because the sentence is too long, the grammar is wrong or there’s a typo somewhere. So that’s something I find quite useful to do in 15-minute bursts.

Do you follow a process when writing papers?

When writing papers, I always start with the figures first by creating a storyboard. I make rough sketches of what figure 1, figure 2 etc. is going to be like and move those around to work out how the story would flow around that.

Oh, I’m a huge fan of storyboarding. It’s one of the first steps of the paper writing process that I teach in my online course, the Researchers’ Writing Academy.

Yeah, I’m big on the storyboarding idea because it gets obvious if you’re missing something. Quite often, you can see that something would be way clearer if we had this or that figure or if we repeated a certain data set etc. I learned storyboarding from my old boss. We used to print out figures, lay them on the floor and literally move them around until we had our story.

That’s so cool.

Now I tend to use pen and paper or a whiteboard. I usually sit in front of the whiteboard with a couple of the students I’m supervising or mentoring and sketch out the story of their papers or dissertations. Often the initial storyboard looks absolutely nothing like the final one.

What do you like about storyboarding?

Storyboards are quite a nice way to structure writing but also to keep students focused and motivated. For students, it can be quite daunting to think about starting to write a dissertation, a larger piece of writing, from scratch. I like to use the technique for results and introduction sections.

How do you use storyboards for writing the Introduction section?

Once we’ve got the final storyboard for the results section, I ask the question ‘what does someone need to know to understand these figures?’ For example, in my research about carbon dioxide reduction, there are all those different products you can make. And so, the pool of literature you could dive into is absolutely enormous. If you’re not careful, you’re going to write a review instead of an introduction to a short paper. I’m aiming to write only as much in an introduction section as is needed to understand the figures. It’s really a simple technique to try to stay focused.

Yessss! This is similar to the process I teach in the Researchers’ Writing Academy. Once we have mapped out the results section, we move to the introduction section. I always say the introduction section needs to have as much information as is needed to understand the specific problem that your study is solving.

What would you say is your biggest struggle when it comes to writing?

Finding enough time to write is a big struggle. In terms of the actual process of writing, knowing when it’s finished is quite difficult for me. When I’m refining my writing as mentioned earlier, it’s very difficult to know when to draw the line and decide that this is exactly what I needed to say. I think the best way for me to get around that is to leave my writing alone for some time. When I get back to it after say, two or three days, I read the text almost as if somebody else had written it. It is like a reset of the thought process that helps to judge whether the paper is good enough to get submitted.

Have you ever worked with a writing coach or editor?

I’ve worked with an editor when we published a review in Nature Reviews Chemistry. That was the journal with the highest impact factor I have ever published in and the experience was different compared to more specialised journals.

I had a really good experience working with the editor. He was very engaged and had a real interest in the topic and in getting the message across. It was actually one of the things that made me realise just how overly verbose my writing style is. When I saw the first pass that he made over one of the sections we’d written, I realised that he’d cut about a third of the text while the content was all still there. Since then, I’ve been much harsher about cutting down my writing.

Yes, I believe that most scientific authors would benefit from working with a good editor at least once, just to understand where they could make the biggest improvement to their writing. So many scientists have only ever gotten feedback on their writing by their supervisors or collaborators but never a professional.

Yeah, that’s true, especially if you’ve worked independently for a while. You tend to get into the habit of writing in a very set voice and sometimes breaking these habits can be productive.

That’s a good point too. Have you ever taken an academic writing course or any sort of professional development in that direction?

I have never had formal writing training in terms of a structured course. But I’ve been very lucky with the people I’ve worked with who have been actively involved in that coaching role. During my PhD, when I wrote my first papers, I’d write a section, and then go through it together with my supervisor. So, my first writing experience was a really strong start. I do know a few people who would send something off to a supervisor, and they get it back covered in your red pen or Word track-changes – these massive swathes of changes can be quite intimidating to see. Instead I was part of the process of correcting the writing.

Oh, that does sound like an amazing experience. I think it also teaches PhD students that writing is a skill they can learn, not something that you’re just supposed to know.

Something that I try to emphasise with my students as well is that if I give them something back covered in edits, it is a compliment. It means that this is an interesting piece of work.

We are talking during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lots of countries around the world are in lockdown and many labs are closed. What are you doing during this time? Do you write more these days?

Yes, in the UK we are in full lockdown. For me, it was quite good timing because I was just starting to look towards putting a fellowship application together and that is a lot of work.

Oh, that IS good timing.

Yeah, definitely. However, I was very close to finishing the experiments for a couple of different projects and don’t yet have all the data to write them up. Perhaps in a month, I’d been ready to write about two papers.

I’m sorry. That’s really annoying.

Yeah, there’s nothing you can do about it. There’s no good time for something like this to happen. But I have also been seeking out a bit more writing from various more senior people in the department, who are writing these larger collaborative grant applications. So, I’ve offered to help out. It’s quite a nice way to explore some other areas of science within the department and to expand the portfolio a little bit.

Great idea! What would you say is one piece of great advice you’ve received about scientific writing or about how to write well?

I think the one I use most is storyboarding, which I was introduced to in my first postdoc. And as soon as I started doing that, I looked back on my previous papers and thought how much easier it would have been if I had used it from the start.

Another piece of advice I use is to always assume minimal background knowledge in your readers. When writing the introduction section, I imagine trying to explain my paper to someone like my friends from my undergraduates who have gone off to do different things. If I were explaining this paper to them, how would I position it? Where would I need to go into detail, so they’d be able to understand it?

Oh, that’s a good strategy! It’s key to think about your audience and to understand the level of detail needed for your target journal.

I think the other piece of advice is something we have been alluding to this whole conversation: that writing is a skill you can learn and that you have to practice. When I was working with the editor on the Nature Reviews Chemistry article a couple of years ago, I considered myself quite strong in writing for a more general audience. I’ve published in a few other general interest journals before but what the editor viewed as being accessible to a broad audience was different from what I thought.

Interesting. It’s for sure crucial to understand that writing really is a skill that requires practicing and getting good advice.

Yeah. It’s something that’s quite intuitive when teaching. When someone’s designing a lecture for an undergraduate class versus for a graduate class versus for outreach, I think they would intuitively adjust the level. It should be exactly the same in writing for a general versus a more specialist audience. We need to be able to assume what one needs to explain and what points need to be highlighted.

So true, we are less aware of our audience when we’re writing than when we’re teaching.

The thing is of course when you’re teaching you can see the glazed eyes and puzzled expressions in their faces whereas when you’re writing you don’t get that benefit!

Yes, that’s probably a huge part of it. We never observe anyone reading our article and being totally confused!

Do you have any plans for the time after your Postdoc?

I’m hoping to work towards an academic position because I really enjoy both the research and the teaching side of things.

Fingers crossed! And thank you so much for talking to me about writing about science, Sam!

Featured publication by Sam

Electrochemical Synthesis of Hydrogen Peroxide from Water and Oxygen

by Perry, S.C.;* Pangotra, D.; Vieira, L.; Csepei, L.-I.; Sieber, V.; Wang, L.; Ponce de León, C.; Walsh, F.

published in Nat. Rev. Chem., 2019, 3, 442

Read the open access preprint version here.

About Sam Perry:

Sam Perry is a Research Fellow at University of Southampton in the UK. In the last six years he has authored 14 peer reviewed journal articles including in Nature Reviews Chemistry, Analytical Chemistry and Chemosphere, and has been involved in a number of collaborative grant applications. He is currently leading a work package as part of a Horizon2020 European Collaboration, working on CO2 reduction with a team of PhD and Masters students.

Connect with him on ResearchGate and Twitter (handle: @Perry__SC)!

About the Interviewer:

I’m Dr Anna Clemens, a scientific writing coach and editor. I help scientists to write better papers in less time. I’d love to support you beyond the blog, please click here for more information.

When I’m not at my desk, I’m probably hiking with my dog/assistant Zuza or sipping an oat flat white in one of Prague’s many cosy cafés.

I’d love to connect with you on Twitter (@scientistswrite) and LinkedIn.