Here’s how you write your paper as a scientific story instead of only reporting your findings.

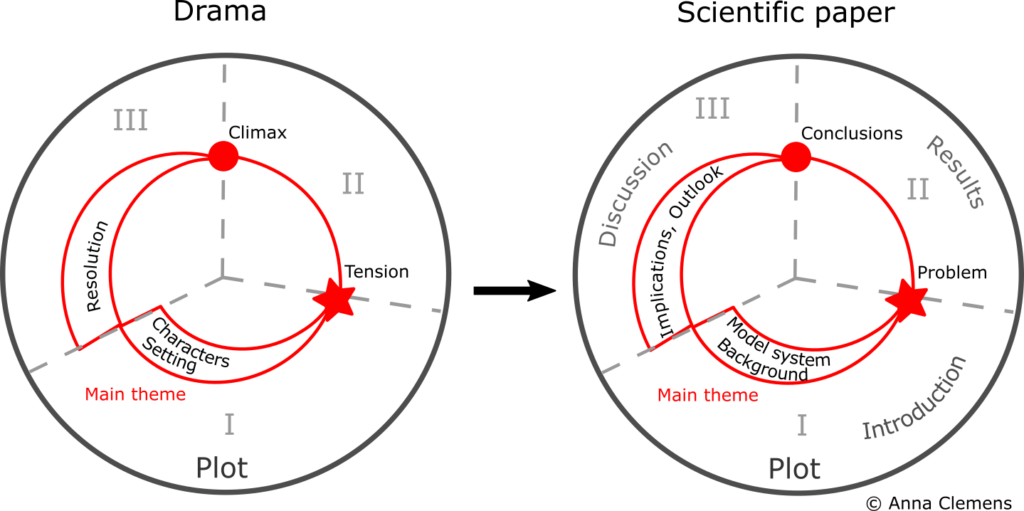

By now, you are probably convinced that storytelling is the way to go, not only in film-making, but also when writing a scientific paper. In a previous blog post, I made the point that for a powerful story you need to have a main theme, characters, setting, tension, climax and resolution elements, and a plot. I also mentioned that you have to keep in mind the aspects of purpose and chronology. So, how do you implement these in your paper?

Let’s start with the main theme. It might sound obvious to you that having a main theme is indispensable. Nevertheless, one of the most common problems that I encounter when working with scientists on their papers is that the manuscripts don’t have a clear motif, or that they have more than one. Therefore, before you start to write your article, try to summarise in one simple sentence what it will be about.

If you find yourself struggling to do this, you probably don’t have a single main theme in mind, but rather several at once. For example, if you want to report about a new method, with which you could measure a link between model system A and phenomenon B that has never been observed before, you can easily end up having two main threads: the novel method and the connection between A and B. This is when you have to decide which line you want to focus on. That said, it is okay to have a side thread in your story, but remember: Simple stories often win.

The most neglected element: tension

Now, what is the main character in your paper? It is not a person but the material, disease, formula, model system or whatever you are studying. The background information around your protagonist that is needed to set the scene then corresponds to the setting element. The reader wants to know what the state of the art is, and where your study fits in.

So far, so good. You are all probably using these two elements in the introduction sections of your articles already. But how about tension? This is, in my experience, the number one missing element in scientific papers. Whoever is reading your paper will understand and care about your findings more if there is a problem that needs to be solved. This is why you should make clear to your audience what has not been understood so far, or where the problem lies with a current interpretation. I advise you to be very precise here, and to avoid general statements. Presuming your paper is about a novel method, the tension element could sound like this: “The sensitivity of existing technique XY, however, is not high enough to detect A…”. Or if your finding is about a new link : “Despite the extensive study of A, it is not known how it depends on B.” If you remember just one thing from this post, let it be the element of tension.

As in a classic story, the scientific paper provides solutions to the problems in the climax part, a.k.a your results section. The “ABT”-technique might come handy here, which Randy Olsson introduces in the book “Houston, we have a narrative”*. The acronym stands for “and”, “but” and “therefore” and it can make it easier to remember the three important story elements of setting, tension and climax. When you describe the background information you will often use the conjunction “and” to connect sentences. You then introduce the tension with a word like “but”, signalling that there is a problem. You’ll then likely use a word like “therefore” to present the solution to the problem, meaning your approach and results.

What’s the big picture?

But the story isn’t finished with your findings, the reader also wants to know what the results mean for your character in the context of the conflict that you’ve introduced. The resolution in a drama resembles the discussion part in your paper. How have things changed for your model system, how does the change affect the state of the art, what implications do your results have for an application or the development of a theory?

If I had to vote for a number two of the most overlooked elements in a scientific paper it would be the discussion, which is often too brief. Perhaps it seems obvious to you what your findings mean. Perhaps you don’t want to exaggerate and you are afraid to make your results look bigger than they are. Or perhaps you haven’t really reviewed the possible repercussions of your study? In order for a reader – and in particular an editor – to understand where your study fits in, they want to know what the limitations of your study are. No study can cover everything, so honesty conveys professionalism. Another aspect of the discussion is an outlook: What should be done in future in this field? Have you started to investigate a follow-up question?

By putting the main theme, character, setting, tension, climax and resolution together, we will get the plot of your paper, in just the way it looks in a drama:

Who thought a drama and a scientific paper could be so similar?! There are just two things left that I want to discuss: purpose and chronology. Purpose is important to keep everything in your story tied together. Why are you doing experiment ABC or analysis DEF and how does it connect to the previous result? Tell the reader. Doing this can also help you to identify experiments or story lines that don’t really fit into the main theme. Chronology is linked to this because by providing the purpose of each different step that you have performed, you are forced to present your results in a logical order.

Now, we’ve translated the elements of a story into a scientific paper. Using storytelling in your papers and proposals, you make it easy for your readers to understand your study. It is also requirement for getting papers accepted in many high-impact journals.

Did you find bits that were new to you or are you already using all these elements in your journal articles? Let me know in a comment below!

Does writing for a high-impact journal feel intimidating? Partly because you’ve never received proper academic writing training?

In this free online training, Dr Anna Clemens introduces you to her template to write papers in a systematic fashion — demystifying the process of writing for journals with wide audiences.